Pin Mill - Helsinki 1992

Choosing a destination for the summer cruise is influenced by a number of factors, not least of which is getting back. If one can remove this constraint, then the range increases exponentially as allowances for bad weather can be reduced or removed altogether. Simply lay up the boat where ever you get to.

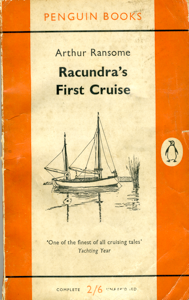

Like most yachtsmen who were brought up on a diet of "Swallows and Amazons" I was desperate to read anything that Arthur Ransome wrote. I devoured "Racundra's First Cruise" but was puzzled as to where it all happened as Estonia and Latvia did not exist in my school atlas. It was disappointing to learn that they were now all part of the USSR and completely out of reach. I would never be able to see the islands of Moon and Worms or beat into the bay of Reval (Tallinn now) under the walls of the fortified Hanseatic town.

It was Jens Marsen, a Pin Mill Sailing club member and of Estonian origins that accelerated the whole plan. Jens and his family had been offered the chance to reclaim property in Estonia which the Russians had appropriated. He and fellow club member, Andrew Bagnall, had been visiting Tallinn and according to Jens the pace of change was so fast I ought to go as soon as possible before the place became over run with tourists.

Another friend and sailing club member, Bryan Cook expressed more than an interest. Bryan is semi retired and able to take on long term sailing trips without too much trouble. He told me that he was fed up with going to the Med as it had become terribly overcrowded, but the eastern Baltic would be a real adventure as no one had sailed there since before the war. "It will be real exploring" he said, "sailing in uncharted waters." Although we did not realise it at the time the latter statement proved quite prophetic.

The key to make it all feasible was that Bryan was happy to stay with the boat allowing me to return to the office and could work her round to a destination if bad weather caused us to run late. The only other consideration was the suitability of Elsi-nore for such a long cruise. Whilst not over endowed with storage space we would never be more than four on board so would have spare bunk space. Also, as she was built in the Baltic she would probably be more at home there than on the East Coast.

The final decider came at the London Boat Show when I wandered over to the Cruising Association stand to ask them if they had any information on sailing in the eastern Baltic. We don't have any books, I was told, but next week Roger Foxall is giving a lecture in the clubhouse on his recent voyage to St Petersburg, Tallinn and Riga. I joined on the spot and the die was cast.

The next problem was getting information about the regulations for entering ex Soviet harbours and charts for reaching them. The Admiralty charts are nowhere near detailed enough to navigate in Estonian waters and, as the whole purpose of the trip was to follow in the wake of Ra-cundra from Riga through the Moon Sound to Tallinn, it all looked a bit grim. Luckily a friend in Helsinki sent me photocopies of Russian naval charts he had managed to find, which gave us half a chance. I just prayed that we would be able to find more charts on the way.

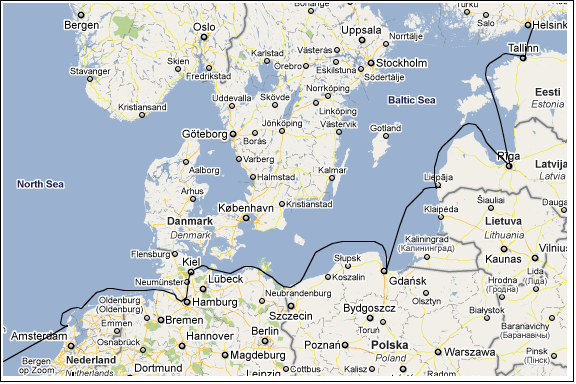

The outline plan was to split the voyage into three legs to allow me three interim visits to my place of work. The first leg would be from Pin Mill to Kiel which we hoped to do in a week. The second, a two week stint, would be from Kiel to Riga which had just opened an international airport. The third and final leg would be from Riga to Helsinki, via Tallinn. I originally planned to try and winter Elsinore in Tallinn but my insurance company did not want to know. They were quite happy with Helsinki though. The ship's company for the first leg would consist of Bryan who had done numerous delivery trips to the Med as well as competed in the AZAB in his Cutlass, Nellie Dean, his friend Liz Tucker from Devon who had accompanied him on several trips, my old friend Peter Henry who had sailed to Amsterdam and Normandy with me and me. Whilst Peter Henry would have to leave in Kiel, Peter Cockayne another Pin Mill Sailing Club member and master mariner planned to join us in Riga.

Our home and mode of transport for the adventure, as we all now thought of it, was to be Elsinore now in her second year of my ownership. She is a Vittesse 35 motor sailor built by LM Marine in Kolding, Denmark, and despite having a wheel house is a powerful sailing yacht with fully battened main and deck sweeping genoa. In 1991, at her first try, she was equal winner of the PMSC class A race series. Her vital statistics are an overall length of 10.7 meters, a beam of 3.3 meters and a draught of 1.9 meters. She sleeps seven in three cabins, carries 200 litres of water, 250 litres of fuel and is powered by a Volvo 4003T die-sel which delivers 43 HP by way of a folding two bladed propeller.

Elsinore was well equipped with instrumentation when I got her being the factory's ex demonstration boat. As well as the usual log and echo sounder she had wind speed and direction indicators, Dana Helm auto steering and twin compasses. I had added a Shipmate VHF and my late mum had bought me a Furuno small ship's radar for my birthday. The only addition for the Baltic was a Magellan 5000 GPS, a wonderful little device which can be hand held and will work off its own battery pack if the ship's supply fails.

A four man life raft was hired from Suffolk Sailing for two months and was complemented by my Avon Redcrest dinghy. Our other safety equipment consisted of a full complement of flares, lifejackets and harnesses. My only real worry was that the best chart we had on board of the treacherous Moon Sound (Muhu Vain) was a sketch map drawn in 1922 by Arthur Ransome!

Saturday 27th June 1992 Pin Mill to Den Helder

We, being Liz Tucker, Peter Henry, Bryan Cook and me, left Woolverstone with much waving to loved ones ashore, at 19.20. The tide was flooding, high water Dover being 21.15, and the wind a light ENE. The plan was to be well out into the North Sea when the ebb set in so as to make the most of our passage to Den Helder.

Following a quick stop at Nellie Dean, to borrow Bryan's first aid kit that we subsequently never used; a wave to the Humbys enjoying the last of the evening sun on Gwenilli, and we were out of Harwich harbour, shaking off the dust of the land by 20.30. The wind was too light, and from the wrong direction to afford us an adequate passage under sail alone, so the trusty Volvo 4003T was kept alight with our main acting only as a steadying sail.

Elsinore, in anything but really adverse conditions, will make a good 6 to 6.5 knots at just a shade over 2000 RPM. We hoped, providing I had worked out the optimum timing for tides, to make the passage in no more than 24 hours.

The weather was fine, visibility adequate and the sea not nearly lumpy enough as to cause any discomfort. By 22.45 we were just off the Shipwash light vessel and altered course to steer 085° for a direct route to the north of Holland.

The night wore on with two hour watches being split between pairs of us. We altered course to cross the shipping lanes, which were, thankfully, enjoying a quiet period as often happens this far north, and then once across, at 05.00, we steered for the Texel light. By 14.30 we were just 3 miles SE of the Texel lightship and about 25 miles from our destination. The wind had not shifted out of the NE but had remained light.

As we closed the channel, Breewud, between the point of Den Helder and the Haaks sand bank, just south of Texel, we joined a stream of pleasure craft returning to harbour. The shore line too, was busy with people enjoying the late afternoon sun, promenading, fishing or just gazing at the boats.

Monday 29th June 1992 Den Helder to Borkum

We entered, what is predominately a naval harbour, at 18.30 to look for the small yacht marina on the western side that, once found, was surprisingly full considering that Den Helder is not a noted harbour for recreation. However, once rafted up I enjoyed an inner glow of satisfaction as the 143 mile passage had been completed in just 22 hours, which meant we had certainly made good use of the tides. We rose fairly early, showered in the Dutch naval officer's club and were ready for theoff by 08.00. Diesel was taken on and we left the harbour, a little before 08.30, into a windless Marsdiep. The sky was greyish but promised to give way to sun-shine later.

The plan was to go north west through the Molengat, a channel of just under half a mile wide, which separates the Haaks sand bank from the south point of Texel, and then to steer north east round the Friesischen Islands to Borkum. All would have been plain sailing, or motoring at the time, were it not for the combined fishing fleets of Den Helder and Texel deciding to use the same channel as us at the same time!

At least thirty fishing boats, going flat out, charged past us through the, now, very narrow channel, causing a monumental wash. We clung on as if rounding Cape Horn trying to keep just outside the channel buoys and miss them at the same time. Morning coffee was served late!

We motored through a flat calm sea past the islands of Vlieland, Terschelling and Ameland. Food and drink came and went as the sun scorched down on a windless sea. The shore, which I had dreamt of being a hostile lee covered in flying spray, now shimmered in a heat haze.

Our course, which was keeping us five miles off shore, bent round to the West; finally heading for the Borkum light whose presence we noted at dinner time. I switched from Admiralty charts to the more detailed Dutch ones and failed to appreciate the exact change of scale. Later this was to nearly cause a disaster that could have ended the expedition there and then!

As dusk fell we motored 075° along the Hubertgat towards Borkum and the mouth of the Ems. The distinctive Borkum light has a range of 35 miles and is easily spotted from the south. The yacht harbour was south east of the town of Borkum marked by a sector light. As we got to within about ten miles of the Ems at 21.30,1 saw a lighthouse one mile south east of the Borkum light that I immediately took to be our sector light. Because I was eased into a sense of false security with the clarity of how everything was unfolding I did not double check the chart and measure the actual distances. If I had bothered to do so I would have noted that the sector light at the entrance to the yacht harbour channel was three miles south east of Borkum and therefore the lighthouse we were now heading straight towards must be wrong.

We were half way across the mouth of the Ems before we all agreed that there wasn't a yacht harbour near the lighthouse. Anyway it did not seem to matter as all we had to do was to motor across to the eastern bank and then turn south, (upstream), keeping close to the shore. We should then see the yacht harbour entrance easily even though, at 23.00, it was pitchy black.

Everyone was now in the wheel house all trying to read the chart at the same time. A strong red light on the bow was identified as a port hand channel marker and I steered towards it. Liz suddenly squeaked as she spotted three, large, unlit mooring buoys close on our port bow. Very strange leaving unlit hazards in a busy shipping channel! I altered course to starboard to get further into the channel; there was plenty of water everywhere as we had arrived at the top of the tide.

We continued to head towards the strong red light now a little more to port. Red channel lights were observed much further away to starboard but as the Ems splits here, to go round either side of the Mowen Steert sand banks, we assumed the lights belonged to the other channel.

Our red channel light suddenly reared up as we closed it, and turned into a sector light as the keel scrunched into a sand bank. We had, of course been motoring up the red sector that was to stop people doing what we had just done. Anyway, as it was high water and no damage done, except to collective prides, we were able to motor off and reorient ourselves.

The channel to the yacht harbour is quite twisty and after our fright we were being ultra cautious. We passed it at first, in preference for the fishing harbour, before the site of masts over a wall persuaded us to go back.

Borkum yacht harbour has a semi-derelict appearance hence our reluctance to enter; the pontoons are steel and rusty giving the place all the atmosphere of a scrap metal yard! We turned in at 1.00 with the intent of a 6.00 AM start to catch the last of the ebb.

Tuesday 30th June 1992 Borkum to Cuxhaven

I was up and about at 5.45, looking in dismay at two Swedish yachts trying unsuccessfully to leave their berth as they were well and truly stuck in the mud. Both were smaller than Elsinore so there seemed little hope that our 1.9 meters draught might slip out.

The rest of the ship's company blinked their way into the misty morning, having been woken by the Swedes' engines. We tried a few desultory tugs at the warps just to confirm that we were in contact with the bottom. So much for the harbour guide stating that a minimum depth of 2.5 meters is always available.

It was a little over an hour later that we managed to break loose from our muddy prison and head north east, downstream against a young flood towards the North Sea. A brief trip ashore had found all facilities locked so we did not feel a sense of guilt at not waiting to pay for our night's rest.

The sector light, now high and dry on the end of a sandy strip, topped by a low mole, seemed far less intimidating in the early morning mist than it had last night when we had slithered to a stop along side it. I was, however, paying particular attention to the channel buoys as we picked our way along. There was again a complete lack of wind and the mist did not look as if it would last much beyond mid morning. The river was free of traffic save for the two Swedish yachts whose wake we were now following.

The Ems flows out almost due west into the North Sea through two channels. To the south the Hubertgat, through which we had entered the previous night, and to the north the Westerems, along which we were now travelling. The northern side of our channel was bounded by Hohes Riff, a sand bank that extends eight miles WNW of Borkum.

The Dutch chart showed a channel across Hohes Riff with a minimum depth of 2.9 meters. If we took this it would save two hours as the flood was now a healthy 2 knots and rising. The channel however was not buoyed and as both Swedish yachts had turned into the Hubertgat we had no guinea pigs to follow. I was still feeling a little unsettled following the previous night's brush with the bottom, but I reasoned that unless I tried it I would never have the nerve to take a short cut again. So, at what I hoped was the right point, we turned north over the shallows with eyes glued to the echo sounder. It took about twenty minutes to cross the Hohes Riff and as soon as the echo sounder had us in 6 meters we started to alter course to the east and begin our long day motoring past the German Friesian islands.

The weather turned out to be much the same as the previous day with hot sun and no wind. We were keeping just out of the shipping channel with the islands in view to port. Both the Decca and GPS agreed as to where we were so navigation was easy.

By 16.00 we were steering a north easterly course across the approaches to the Jade and Weser towards the 'Elbe 1' light vessel. The sea was now busy with shipping and occasional yachts to keep us company. The heat haze was such that we would sometimes get a mirage when looking at a large ship. The effect was for the middle of the ship to disappear into the water leaving just the bow and stern visible. It was very weird.

By 19.00 we were following the well-buoyed channel into the mouth of the Elbe as the tide went slack. It was low water so we had the flood to look forward to as progress against the tide here is very slow. To the south acres of mud flats, covered in wading birds glistened in the sun set. It all looked very tranquil. Only the many wreck markers on the chart illustrated how it might be in a strong onshore blow.

The entrance to the yacht harbour, just east of the ferry terminal, was negotiated without drama and a marina berth quickly found. We even had time for a beer in the yacht club although the surly staff would not change us coins for the phone box and were extremely prompt at shutting. Anyway it was a much happier ship's company than the previous night that turned in after demolishing our whisky supply.

Wednesday 1st July 1992 Cuxhaven to Brunsbiittel

Whisky and Gin at £6.00 a litre makes Cuxhaven one of the cheapest ports for duty free. Stocking up the wine cellar, therefore, was the day's main objective. The vendor operates from a warehouse in the back streets of town close to the harbour and all goods are delivered to the marina. It is not easy to find though having been once I could probably find it again, as Bryan now did for us. Peter had managed to call home to learn that his presence was urgently required at the office, so sadly had to take his leave to catch the ferry from Hamburg back to Harwich.

Liz, Bryan and I went back to town to do some food shopping and take a leisurely fish lunch at one of the many outdoor cafes. We spent the afternoon reading on board, waiting for the booze to arrive. At 17.00 the delivery van appeared and we quickly transferred the cases to Elsi-nore's hold.

The tide was now ripping out of the Elbe at three to four knots. A strong onshore breeze though had blown up which would give us a dead run up the river the fifteen miles to Brunsbiittel and the entrance to the Kiel canal. We sorted ourselves out and poked our noses out of the harbour at 18.00. The wind had brought with it mist and rain making visibility quite poor. The radar was a great comfort for buoy spotting, as we huddled in the wheel house out of the now teaming rain, motor sailing under a reefed genoa.

It took us five hours to do the fifteen miles. During which time we were passed by a stream of vessels heading for the sea, including the Harwich ferry from which Peter was waving unsuccessfully at us.

Entrance to the lock approach is governed by light signals, as is entrance to the lock itself. Having successfully crossed the western approach and been avoided by the pilot vessels darting around, worrying their large charges into order, we saw a German motor barge and a yacht loitering close to our entrance. The lights on shore turned to green and white allowing us to enter the approach and then as we did just that the lock light turned to green so that we could motor straight in.

With just the three of us to lock through it seemed only minutes before the gate to the canal was open and we were motoring out, following the German yacht round port, crossing again the western lock, into the Brunsbiittel yacht harbour. Yachts are only allowed to traverse the Kiel canal during the hours of daylight, and must have an engine running at all times.

We slept, as ships towering above us slid into the western lock, with a thrill of excitement that we were now in the gateway to the Baltic.

Thursday 2nd July 1992 Brunsbütel to Kiel

I had always imagined the Kiel canal to be highly industrialised, busy with shipping and generally an unpleasant experience to get over with as quickly as possible. It was therefore with some feeling of trepidation that I awoke and hurried ashore to pay the canal fee at the lock control. Despite what Macmillans and the CA handbook say yachtsmen can only pay at the Kiel end for traversing the canal so my expedition, which had taken some time, was to no avail.

The Kiel canal is 53 miles long, sailing is only permitted with an engine running and berthing alongside the banks is not allowed. As well as Brunsbiittel and Kiel, there is a yacht harbour at Rendsburg, 40 miles along.

It was 9.15 before we finally got underway the delay being caused by my trip ashore and the discovery that a fender was missing. We searched around the marina but could not find it, so surmised that it had been dropped in the lock the previous night.

Soon, a lock full of ships slowly overhauled us but as the speed limit is 15KPH, a little less than 8 knots, the wash was negligible. As it takes quite some time to turn a lock round, because before ships can come in the others have to get out, our own 6 knots meant that we would not be bothered that often with passing vessels.

A fresh breeze from the west blew the clouds away and encouraged us to set all sail. The canal banks took on a rural aspect and with the engine ticking over we settled down to a delightful day's sailing. Far from being the industrial horror that I had imagined the canal is not unlike the upper reaches of the Thames, with some spectacular English like countryside.

I was glad that we were able to motor sail as we were quite low on diesel following our slog against the tide the previous evening, and I had been a little worried about making Rends-burg. Elsinore too seemed pleased at last to show off her sailing prowess and surged ahead with every puff of wind. We soon caught and passed the yachts that, earlier, had been dots on the horizon all of whom now copied our example and bent on sail. One of them, 'By Jupiter', was manned by three bearded Brits who, at 11.00, were well into the cocktail hour. With plenty of cold beer in the fridge and a now hot sun we sped along quite content with our lot.

Rendsburg came and went but such was our economy of fuel that a stop was unnecessary. Just before the locks at Kiel the canal becomes more river like and meanders through a couple of bends. A traffic light system on the shore controls a one way passage so that large vessels have plenty of room to negotiate the bends. These were flashing red as we approached, halting our progress and allowing the yachts we had overtaken to catch up. Once the long barge, which had been the reason for our delay, had passed we set off, now in a group and minus sails.

At 18.00 we entered the lock at Kiel along with three other yachts and one motor boat. Luckily the crew of 'By Jupiter' had been through the canal before and knew the system. First one has to go ashore to a kiosk just before the lock and buy a ticket. Then one must go to the lock control office on the other side of the lock, climb three flights of stairs and get the ticket stamped. The logic of this two stage procedure escapes me but once completed the lock gates were opened allowing us out into the Kiel fjord.

I had spent two very happy sailing holidays in the Kategat when we lived in Norway and so it was a bit like coming home to be back in the southern Baltic sea. And what a home coming, the whole place was sparkling in the early evening sun. Yachts and boats were everywhere and there seemed to be no better place to be.

'By Jupiter' was bound for the British Kiel Yacht Club as we were so we followed her round up the western shore looking for the inconspicuous entrance. Once found we were soon tucked up in a berth alongside Avalanche, one of the splendid ex German 60 meter yachts now owned by the British army. Gin and tonics were taken in the cockpit with the crew of 'By Jupiter' that had come from the Medway, and so ended a splendid day and the first leg of our adventure.

Friday 3rd July 1992 Kiel

The British Kiel Yacht Club is a splendid place. Its primary purpose is a sailing facility for die British army but yachtsmen of all nationalities, except German, are welcome to use it. The bar is cheap and friendly, duty free goods may be obtained and an inexpensive clothing shop may be used. A fleet of Halberg Ras-sey 29s for use by army personnel is kept here both for cruising and instruction. The other attractions are four ex-German meter yachts which Hitler had built for German naval officers to learn sailing in. These were acquired by the British army after the war as part of the war reparation. They are kept in beautiful condition and can be chartered by members for £60 a day including a skipper. As the smallest sleeps ten, this is a pretty good deal.

It was a sad Friday for me as I had to leave Elsinore and catch the Hamburg ferry back to Harwich. Liz and Bryan were going to stay on and sail round the corner to Fehmarn island, via Denmark, where I would meet them in a week's time. One of 'By Jupiter's' crew men was also going back on the same ferry and so I had some company. The skipper, Roger, ferried us to a quay next to the railway station and so ended the first part of the voyage.

Tuesday 14th July 1992 Fehmarn

I flew to Hamburg and then caught a train to Oldenburg. A bus took me the rest of the way to GroBenbrode which is where I hoped Elsinore and crew would be. This marina, which is on the mainland just south of Fehmarn, had been recommended to us by the skipper of "By Jupiter', who had claimed that it was cheap and friendly. It turned out to be both of these but lacked any diesel which was a pain. Next to it was another marina that is the base for Dehler yachts.

I arrived at 16.15 laden down with charts, clothes and a huge pork pie. Liz spotted me and I was soon reunited with Elsinore. The pork pie was a godsend as Bryan and Liz had been sailing round the Danish islands and the store cupboard was running very low. The harbour master and a lady friend he had picked up on his rounds came aboard for a drink, not for the first time that day judging by his happy disposition. The lady, on hearing of our food shortage, kindly offered to run us to the supermarket in the morning. An offer we were pleased to accept, although I was a little aggrieved at the delay this would cause to our sailing. As we also needed to take on diesel which meant a trip to Fehmarn anyway, I stopped worrying and got my mind set for a day's delay.

Wednesday 15th July 1992 Grolienbrode to Fehmarn

The weather was not as pleasant as I had left it and whilst the wind was from the west it was gusting 6 and bringing rain with it. I unfolded the ships bicycle and rode to the bank whilst Liz went to the supermarket to replenish our store cupboard.

By midday the rain had stopped although the wind was still quite fresh. I decided that we must move to Fehmarn and take on diesel so that we could get an early start the next morning. We could not afford to lose another day if we wanted to make Riga by Saturday week. We left GroBenbrode at 14.30 and with the wind now down to a 4 made an uneventful crossing of the ten mile straight to Fehmarn and were in the marina at 16.00.

Fehmarn is a German holiday resort dominated by large blocks of holiday flats looking out over the sound; very tasteless. One benefit of holiday resorts is that they are usually well catered for with restaurants. After taking on diesel and finding a berth we treated ourselves to a meal ashore and looked forward with anticipation to the next day and East Germany.

Thursday 16th July 1992 Fehmarn to Stralsund

The plan was to sail to Stralsund near the island of Rugen and it was with a new feeling of excitement that we poked our nose out to head east. Ahead lay the old East Germany and the start of the real adventure.

The wind was a light westerly and with 75 miles to cover before dark the engine was kept hard at work. The approach to Stralsund through the narrow winding channels round Rugen looked quite tortuous on the chart and possibly unlit.

We were skirting the main east west shipping lanes that eventually split to go south east to Rostock and north to Sweden. By 10.30 the grey skies had lifted and the wind freshened to a nice force 3. The engine was stopped and with the genoa boomed out we made good progress. By 12.00 Bryan and I were bored with this simple sailing and decided to put the spinnaker up. The cook was not altogether happy with this decision and her confidence in our spinnaker flying ability was not helped by us making a complete pig's ear of hoisting it.

Once set, the spinnaker certainly helped us along and with the wind now a generous 4 we started to fly. It was all great fun but what we failed to notice was that the wind strength was still increasing. A German yacht beating towards us, heeled well over, should have given us clue, but all I could say was that we must be looking rather spectacular. No sooner had I spoken than Elsinore decided that she had had enough and broached hard to port. Liz squeaked and demanded that we remove the spinnaker forthwith, an instruction we would dearly have loved to have carried out. The problem was that the spinnaker pole had worked its way so far up the forestay that even I could not reach it to release the guy. All the while we kept broaching our way into the shipping lanes, which were now quite busy. Bryan finally had the great presence of mind to let the spinnaker guy fly so that it all went through the pole, allowing me to drag the thing down by the sheet.

With our simple sail plan restored we returned to a less stressful mode of sailing and deemed it safe for Liz to make lunch. She was heard muttering about waiting until we were asleep and then cutting up the spinnaker into tiny pieces!

At the eastern tip of Mecklenbur-ger Bucht is the headland DarBer Ort where our course changed to due east. By 15.00 we were heading straight for Rügen and the narrow channels which wind through a maze of waterways to Stralsund. It was a sunny afternoon and a Dutch tall ship heading the same way made good sport as we slowly overhauled her.

It was 18.30 when we finally turned south down the narrow buoyed channel to enter the waterways that separate Rügen from the mainland. The whole area is wonderful, not unlike a huge, wooded, Walton Backwaters. Stralsund though is nothing like Walton, with an impressive skyline and harbours each side of the lifting road and rail bridge to Riigen.

It was just turning dark when we motored into the western harbour to raft up alongside a West German yacht, the crew of which informed us that the bridge would open at 8.00 in the morning. With this welcome knowledge we stepped ashore for the first time in East Germany to try and phone home.

Friday 17th July 1992 Stralsund to Dziwnow

We were up early in plenty of time for the 8.00 bridge along with a dozen or so other yachts, mostly German. On the stroke of eight the combined road and rail bridge started to lift to let the west bound traffic through first, and then us bound for Poland.

The eastern side of Stralsund was quite different in character from the old town we had just left. Here there were shipyards and docking facilities. Six new cargo vessels, each with a hammer and sickle emblazoned on their funnels waited forlornly in dry dock for their owners to come and collect them.

Our course took us south east at first along a rural meandering channel, not unlike the Norfolk Broads. The wind, a light south easterly, was of no practical use, but it was hot, sunny and very pleasant to be on the water in such a scenic and tranquil place. I could quite happily have spent a week here exploring the myriad

of delightful looking channels that constantly beckoned one away from the intended route. The money and commercialisation have yet to move into this part of Germany and it is still delightfully unspoilt.

I had talked to the skipper of a large German motor cruiser in Fehmarn marina about the waters of Riigen. "It is grossly over rated" he had said, "nothing there, no shore power, no die-sel, water or proper marina facilities." Talk about one man's meat, etc.

At 10.30 we had finished our meanderings and entered the Greifswalder Boden, a semi enclosed expanse of water 20 miles by 20 miles. It is bounded to the north by the island of Riigen, to the west by Stralsund, to the south by Greifswald and to the east by a series of sand banks. Our course was due east and with the wind still in the south east we allowed ourselves the luxury of an hour's sail. There were several yachts on the water though barely enough to make a quorum so there was no feeling of it being crowded.

The detailed German charts are excellent being similar in quality to the Dutch books of charts. The channels were well buoyed too so we had no difficulty in threading our way round the sand banks, to leave the inland sea for the Baltic. It was noon and the sunny morning was replaced with a grey threatening sky and freshening south easterly. Our course was of course south of east so we motor sailed into a short lumpy sea that the Baltic seems able to throw up at a moment's notice.

I had hoped to make Kolobrzeg our first port of call in Poland as it would have got us a good way on to Gdansk. It was eighty miles away though, 13.30, and with the wind now blowing a five on the nose a night passage was not the most popular suggestion. I scoured the chart for somewhere more accessible and settled for Dziwnow as it was the last harbour on my German charts and being 40 miles away should be reached in the light. The Baltic Pilot described Dziw-now as a small fishing harbour at the mouth of the Rze-ka Dziwna with a minimum depth of 4 meters.

We plodded on butting our way through the choppy water with little enjoyment. Thankfully at 19.00 both the wind and sea subsided to give way to a late sun. At 20.00 we passed the offing buoy and could clearly make out the entrance between two moles, bordered on each side by sand dunes and pine trees. The beach was quite crowded with groups of people sitting or strolling by the water's edge. The moles too were busy with people fishing, gazing out to sea or as we appeared gazing at us.

Once past the moles the waterway became a river with pretty, wooded banks but no sign of any harbour facilities. It bent round to the east and just round the corner to port was a landing stage for a small chalet type building decorated with a collection of bunting like a sailing club house on regatta day. There was no sign of life there so we slowly motored on wondering what we would find next.

On the starboard bank a small creek opened up with a grey high speed motor boat tied up alongside a large houseboat. The motor boat looked as if it might be official so we kept clear. Ahead of us a pontoon bridge rattled with crossing traffic and prevented any further passage up stream. To port though, a small harbour with about six or so fishing boats and two yachts looked a good bet and so we nosed in and prepared to tie up close to the two German yachts. A man who I assumed was off one of the yachts hailed us and in perfect English told us that we must go to the immigration office before coming ashore which turned out to be the chalet with the bunting. We did as he suggested and so began our first experience of bureaucracy in the East. Not only do you have to clear customs and immigration on entering a country you also have to clear them on entering and leaving every harbour!

We were a little disappointed at first that the yachts had gone as we assumed our English speaking guide had been on one, but not so. He was the engineering officer on Mistral, a Polish lifeboat stationed at Dziwnow. In Poland the lifeboat service is professional and these powerful craft with a full time crew are on permanent standby up and down the coast.

We had just tied Elsinore up when Zbyszek, as he was called, came to see us. His excellent English, we learnt, had been acquired whilst working on a North Sea oil platform support vessel for a Scottish company. He seemed keen to practise his English and offered to provide diesel and a lift into town for a meal. We gladly accepted both and were soon enjoying the best meal in town with German larger, Polish Vodka and all for £2.50 a head. We all agreed that we were going to like Poland!

When we returned to Elsinore I was a little puzzled as to where the diesel would come from as there was no sign of any pump in the harbour. "Don't worry" said Zeb, "I bring the diesel after mid night, only one Deutsche Mark a litre." The diesel when it appeared came in a 25 litre, grey, jerry can suspiciously similar in colour to the grey hull of the lifeboat. Whilst in favour of free enterprise, I just hoped that the life boat didn't run out of fuel on a call out.

Saturday 18th July 1992 Dziwnow to Gdynia

Despite being one of the smallest harbours we visited, Dziwnow turned out to have the last reasonable shower and loo we were to find before Helsinki. The rest were not for the faint hearted!

The plan for the day was to make for Darlowo, a port I had no charts for and knew tittle about other than it was 80 miles away. At Elsinore's top cruising speed that would take between thirteen and fourteen hours. I was eager to get off because even though the days were incredibly long, I still wanted to have time for a look around.

The skipper of the lifeboat, a splendid, sixty-five year old Pole with a long grey moustache and twinkley eyes, advised me to go half a mile north of Darlowo before turning in, as an uncharted sand bank blocked the entrance from the south. He thought that the harbour would be quite suitable for Elsinore. I thanked him for his advice and hoped that he was getting his cut of the diesel profits.

Our attempts at an early start were frustrated by the immigration and customs officials who took an age to sort out their forms even though they had only filled them in the night before. It was therefore 9.30 before we poked our nose out in a grey misty morning and settled down for the day on a north easterly course. The wind from the south west was at last in our favour if a little too light to sail unaided. Visibility was not much more than 2 miles so litde was seen of the coast line or anything else for that matter.

At 14.00 the sun broke through and the wind veered to the west and freshened to a nice 3. All sails were set and Elsinore romped along, glad again to show off her sailing prowess. We could now make out the coasdine but it all looked fairly flat and featureless so we had not missed much.

Koloborzeg, the port city and holiday resort at the mouth of the Parseta river, was passed without the need to dodge any shipping wanting access. The land then started to curve away from us to the east as we crossed the shallow bay at the heart of which is the industrial town of Koszalin. It was by then late afternoon, and our destination was two to three hours away on the other side of the bay. I ventured a thought that perhaps we should not waste such a good wind but sail on through the night and thereby make Gdynia by the following afternoon. All agreed and we settled ourselves in for a night passage up the Polish coast.

The original setders of Poland were Slavs who predated even the Teutons as evidenced by Berlin and Leipzig being Slav names. The country has had a glorious past having saved Europe from the Tartars at the start of the middle ages, and from Islam at the end, when King Jan Sobieski lifted the Turkish siege of Vienna with a force of Hussars. The coastline from Swinoujscle on the western border to Gdansk in the east is just 300 miles. A far cry from her hey day when she was the largest kingdom in Europe stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea. But, like all great empires, her neighbours have gradually whitded her away and finally partitioned her down to her current size.

We were now making excellent time, speeding past the coast at 7 knots in the gusts. At 20.00 the wind was up to 5 and as we needed to make a little more easterly course the main was dropped in favour of a relaxed night run under a partly reefed genoa.

It was not quite as relaxed as we might have wished, for as we were beginning to recognise, as soon as the wind was up to 4 or more, a short sea would kick up making the vessel's motion most unpleasant.

Bryan and I did two hour tricks at the tiller whilst the cook dreamed up the following day's menu. At 6.00 the wind died away and the engine was pressed into service which was just as well as we had no hot water. Breakfast was enjoyed in a sun bathed cockpit, just like being on holiday again.

As we continued, on our now south easterly course, two naval vessels were spotted at rest on our starboard bow. One was a gunboat and the other a submarine. I double checked our position, which was half a mile north of the prohibited area, but altered course a little more north just to be safe. Both vessels started to move towards us the gunboat moving round our stern but, more alarmingly the submarine dived at first so just its conning tower could be seen, and then down to periscope depth. I could just see the headlines, 'Unfortunate accident in Polish Naval exercise area as British yacht is regrettably sunk by submarine!' We waved cheerily at the gunboat, hid all cameras, held our breath and tried to look like we were on holiday. It must have worked because the periscope zoomed off at right angles to us, back to the prohibited area followed by the gun boat.

After this, rather unnerving experience, it was pleasant to relax again and enjoy the rounding of Hel, an old fishing village on the south east tip of the peninsula, as we started across the Gulf of Gdansk to Gdynia. I had chosen Gdynia for our port following a conversation with Roger Foxall, author of 'Sailing to Leningrad', at a CA lecture. "Gdansk," he had said, "has the beauty but Gdynia has a marina." This was now 10 miles away as we passed Hel.

Despite its proximity to Gdansk, Gdynia is Poland's second largest port and one of its newest cities. The reason for this is, that following the First World War, Gdansk, which had been Poland's only outlet for water born commerce, was put under the control of The League of Nations. Fearing that this would seriously affect their ability to trade the Poles quickly built another port as close as they could. In the 1920s, the transformation of the fishing village of Gdynia to the busiest port in the Baltic was started, and by 1938, 13,000 ships a year were using its facilities. We now experienced the busiest concentration of shipping since Rostock, not a worry, but enough to keep one alert.

Keeping a watchful eye on two fishing boats speeding towards the middle entrance, we eased towards the eastern end where we could now see the tops of masts. It all looked very sparkley in the late afternoon sunshine and for once the hinterland was undulating with an actual cliff behind the harbour. The main was dropped and we turned into the yacht harbour past a sandy beach underneath a wooded cliff face. To port was the harbour master's office with a landing quay alongside and to starboard the harbour wall was full of locals fishing. Knowing the procedure for checking into Polish harbours we eschewed the beckoning marina berths and made fast to the harbour master's quay.

The harbour master, a grizzled sun burnt character luckily, spoke some English. He confirmed that we should wait at the quay for immigration and customs and then enquired as to my requirements for water and diesel. I confirmed that I would need both and asked where the fuel berth was located. "As soon as the immigration people have been I will arrange the diesel, no problem" he said. "You can fill up with water here."

Meanwhile outside the harbour master's office a couple of characters were in conversation with Bryan. The younger of the two spoke perfect English and was asking if we wanted a taxi. "No" said Bryan, "we have only just got here and have to wait for customs." "Will you want one later" he asked? "I don't think so" said Bryan, "we will probably stay on board to night." "Will you want one tomorrow" persisted the young man, "my father will drive and I will give a commentary on the local sights, we can show you the concentration camp"! This was not at all what we had in mind and started to beat a hasty retreat on board. "How about some diesel?" he enquired. "I have already ordered some" I stated. "I can probably get it cheaper" he went on, "one Deutsche Mark a litre." "Sorry, too late I am already committed" I said as we climbed on Elsinore and claimed sanctuary in the cockpit.

Just then the customs man arrived. He was a nervous looking individual with heavy rimmed glasses, a dark moustache and wearing a black overcoat. Despite the heat of the afternoon he refused offers of a seat in the cockpit and insisted that we go below to the saloon.

"The immigration officers are here" called Bryan from the cockpit. My friend from customs quickly stuffed the cans of beer and packet of fags into his briefcase and muttered about how all the customs formalities were now completed. He nodded to the two grey uniformed officials in the cockpit as he made his way ashore.

"Would you like to sit in the cockpit or go below?" I asked my new guests. "We go below" one of them replied. Here we go again I thought more beer and fags for the boys. Once we were seated I asked them how many beers they would like. "No beer" snapped the spokesman sternly. Whoops I thought I've got it all wrong. "But have you any cigarettes?" he continued in a more obsequious voice. That's more like it I thought, "Yes I said, "you may have a packet each but please don't smoke in the cabin." They muttered their thanks and then got down to the business of filling in the immigration forms and stamping my crew list. Once completed we shook hands and off they went. It had taken three public servants to check one holiday yacht at a cost to us of sixty cigarettes and four cans of Becks Beer.

Having seen the immigration people go, the harbour master beckoned me ashore. "Come" he said, "we will go and get the diesel." I followed him along the harbour wall to the shore where there were a number of sheds and a large club house. He entered one of the sheds with me at his heels and started to speak to a fat man in dark glasses who was smoking furiously. My presence seemed to make him nervous and he puffed away all the harder. The two of them gabbled away and eventually the harbour master said that we should go outside. He lead me out and round the corner to the front of the shed. After a few minutes the fat man appeared with two 25 litre jerry cans that were obviously full from the way he carried them. The harbour master gestured to me to pick them up. I picked up one and left the other for him to carry, free enterprise is all very well but I was beginning to expect a little more value for my money.

Bryan carefully emptied the 50 litres of fuel into Elsinore's tanks, handed back the cans to the harbour master and then we motored across to a berth in the quite full marina. There were eight yachts on the foreigner's pontoon, from Germany, Finland and Sweden but we were the only Brits.

Liz had just started cooking supper and Bryan and I were tidying up below when a uniformed bloke climbed aboard and announced that he was the harbour master. "But we have just seen the harbour master" I said. "Yes" he said, "we have different times of duty." I looked over towards the office we had just left and could see harbour master one still looking very much on duty. "What can I do for you?" I asked. "Do you need any diesel?" he enquired. "No thank you" I said, "we have just got some from the other harbour master." "How about a taxi?" he continued. "No" I said we are staying on board tonight." "Tomorrow" he persisted, "I will take you on a sight seeing tour." "I thought you were the harbour master?" I said. "I am" he replied, "but tomorrow is my day off and I drive a taxi." I gave in, "OK tomorrow you can take us to Gdansk."

All the time he had been talking to us, harbour master two had been nervously twisting a black bag around in his hands. He now leaned forward conspiratorially opened the bag and thrust what looked like a yellow, plastic necklace into Liz's hand. It was really amber as Poland is the source of some of the world's purest. Liz was not impressed though and put it back in his bag. He next fished out a small black jar, "Caviar" he exclaimed, "only $8.00!" So far, everyone we had met in Gdynia had tried to sell us something and I was getting very fed up of showing polite interest. I suddenly didn't want to know, even if he was going to offer the finest Beluga caviar at £5 a ton I just wanted him off the boat. "Look" I said, "we don't want to buy anything we just want to be left in peace to eat our supper, good bye." "But what about the taxi ride tomorrow?" he cried. "I've changed my mind" I said, "we will catch the train, good bye." Both Bryan and I stood up and whilst still smiling made it very clear he should leave. He complied, looking nervously around the harbour to see if any officialdom had observed his attempts at trading. But there was no sign of any gendarmes, they were probably in the car park siphoning diesel out of his taxi!

We sank back in the cockpit to take stock of the situation. "I'm beginning not to like this place" I said, and that was before I had seen the loos! We ate supper, changed and after carefully locking everything up wandered ashore for a stroll and a beer.

Our spirits were not lifted by the town of Gydinia, its hasty construction evidenced by the drab architecture and uniform layout. We found a smart looking bar but stayed for only one drink when we realised we were being charged the equivalent of £1 a bottle. In a country where the average wage is £120 a month this seemed like a definite rip off.

The unit of currency in Poland is the zloty, meaning gold, and the exchange rate, when we were there, was 2500 to £1. It was difficult to cope with the order of magnitude as most things, outside our bar, were very cheap but seemed to cost a lot as one counted out thousand zloty notes.

Despite our rather downbeat mood we resolved to give Gdansk a chance in the morning as it was supposed to be one of the milestones on the voyage. We turned in hoping not to dream of hordes of harbour masters all trying to pour diesel and caviar into Elsinore.

Monday 20th July 1992 Shore leave in Gdansk

The loos and shower were hidden in the depths of the Yacht Club Polski W Gdynia, so well hidden that I doubt if any cleaner has ever found them! Having survived this ordeal we breakfasted aboard and then set off for our sight seeing tour of Gdansk on what was a hot, sunny morning.

We got a $15 quote from the taxi rank for the ten mile journey to Gdansk. Whilst normal by western standards, this was probably way over the top for Poland as the train ride back only cost us 30 pence each! Time however is valuable and we took the taxi as the most expedient option.

Whilst portions of the original building materials were recovered from beneath the rubble most were incomplete and had to be painstakingly matched. The success of this operation is a great credit to the determination of the Polish people to make their fine city rise again from the ashes. It is little wonder then that this same determination gave birth to the Solidarity movement that finally liberated the whole country.

We climbed the tower of St Margaret's cathedral, the largest in Poland and, we were told, the only one to have stained glass, and gazed out over the fine roof tops to the Motlawa canal. The tall houses, four or five stories high are mostly Gothic or Renaissance in style. Walking amongst them along the narrow cobbled streets one can easily imagine what it was like as a bustling, prosperous port, a corner stone of the Hanseatic League.

The Motlawa canal runs from the Vistula river straight into the heart of the old town and used to be the sight of the main port. The Zuraw, a huge, much painted, wooden crane, having been faithfully restored, dominates the scene. Just above it, alongside the old town wall lay three yachts. It might have been noisy during the day, and there might be no faculties (!) but there were also no harbour masters trying to flog you their grandmother! I vowed next time, for such was the attraction of the place that there might be a next time, I would berth here and miss out on the pleasures and smell of Gdynia.

We took a shuttle ferry to the island opposite the Zuraw to see the maritime museum and one of the last coal burning ships, the Solidat. Launched in 1948, the Solidat houses a vivid photographic history of the Solidarity movement.

Inspired by what we had seen the last visit of the day was to the gates of the Lenin shipyard, outside which is a memorial to the people, men and women, who had been killed there when peacefully protesting against price rises.

We rejoined Elsinore that night feeling a lot more positive about Poland in general and Gdansk in particular.

Tuesday 21st July 1992 Gdansk to Liepaja

Clearing customs and immigration as usual cost us time, four cans of beer and forty fags. It was 9.00 therefore before we finally got away on a north easterly course with a nice easterly 3 and a hot sunny sky. The plan was to head north, out of Polish waters, into Lithuania and play it by ear. I had now run out of detailed charts until we reached Riga so it was very much a voyage into the unknown.

We motor sailed past Hel and spotted some navy frogmen on the beach with a large rubber dinghy looking as if they were in some kind of training exercise. I steered well away just in case they decided to use us as a pretend enemy and try and stick semtex to the hull!

It was now that the engine gave its first falter. I have to say that I have been blessed with the most reliable engines both in Ha de pa Bade and Elsinore. During six years of sailing Ha de I never had a moment's trouble, so when Elsinore's Volvo 4O03T suddenly slowed I immediately thought the prop was fouled. I throttled right back and then eased her into reverse to try and clear whatever was the problem. We hung over the stern looking in vain to see a plastic bag or nylon line pop to the surface. I put her into forward again and she responded at once so all seemed well.

With a fair wind we were able to stop the engine and bleed any air in die system whilst sailing. I began to wonder about the purity of Polish diesil oil and was secretly regretting my oversight in not bringing any spare filters.

By midday the shoreline had disappeared as the blue sky and sea merged into a greyish line. It appeared briefly at 18.00 when the point of Mys Taran that delimits the north western end of the Gulf of Gdansk came into view and then turned due east to the Neringa peninsula.

This thin strip of land, which makes up more than half of Lithuania's 55 mile coastline, separates the Kursiu Marios lagoon from the Baltic. It is reputed to be quite a beauty spot with fine sandy dunes backed by pine forests. Unfortunately our tight time schedule prevented any exploration, but that did not stop us hoisting the Lithuanian courtesy flag to celebrate our first Baltic state.

The wind started to veer south east and freshen slightly, allowing us to ease sheets and watch the speed increase at a most satisfactory rate. This was much too good to stop so we settled down to another night passage forgoing the chance to call at Lithuania's main port of Klaipeda. In retrospect this was a mistake, as we learnt from some Danes later on that it is well worth a visit, though quite how easy it would have been to enter at 3.00 in the morning I am not sure.

The wind stayed fresh all night and in the first hght of morning I started to wonder where we might stop. The only port I had any recent information on, before Riga was Ventspils in the north of Latvia. Roger Foxall stayed here in his yacht Canna and found it most unpleasant as it is a busy trading port with the constant wash of tugs pounding you onto an unfriendly quay side. Another option was to make an early stop at Liepaja half way up the Latvian coast.

In fact I couldn't tell from either the charts or my Michelin road map which country Liepaja was in, they both just stated USSR. Luckily I had my copy of "Racundra's First Cruise" on board which shows the world as it was before the war.

The Baltic Pilot informed me that Liepaja was a large port with three harbours and a canal that was navigable up to the old town. It also said that it was well protected by a mole that ran a mile out to sea and had entrances from the South, West, and North. Unfortunately it also stated that as it had become home to the Russian Baltic fleet the latest information had been gathered in 1960! Ah well, we thought, it can't have a Russian fleet in it now, and the prospect of lying alongside an old town quay decided the matter, Liepaja it would be.

There was absolutely no sign of life except for a solitary gun boat speeding towards us! Here we go again I thought an unfortunate accident as British yacht is blown out of the water whilst trespassing in prohibited waters. The gun boat stopped about 200 meters away as several pairs of binoculars inspected both Elsinore and us. The radio suddenly burst into life, "Yacht, steer zero degrees." This course would take us out of the northern entrance. Fair enough, I thought, they don't want us here so we had best go. I had just set a course for the exit when the radio spoke again, "Yacht, sorry, mistake, steer one eight zero degrees to harbour channel." We waved enthusiastically at the gun boat from whence we assumed the instructions were emanating and steered towards the end harbour.

Ships lying two and three deep were moored each side of the channel but all looked dead, crewless and covered with rust. It was like sailing into a ship's grave yard, very spooky. A little way along another harbour entrance opened out to port also filled with vessels, but this time they were frigates, cruisers, and destroyers all brisling with modern weaponry and young, Russian sailors The fleet was still in town!

Our Latvian friend, Igor, explained that he was part of the Latvian Sailing Association and that until two weeks earlier Liepaja was a military city, closed to all foreigners. It was a good job we had not started our holiday earlier or perhaps the reception from the gun boat might have been somewhat more hostile. His uniformed companion turned out to be immigration who seemed quite pleased to be checking in foreign vessels again.

After a few minutes another young man also in uniform climbed aboard and sat with us in the cockpit. "Who is he?" I asked. "He is the customs official" said Igor, "but no one has given him any forms yet so he will just sit here for a while and then go back." "Why does he bother?" I asked. "Because it is his job" replied Igor.

We finished the formalities quickly, shared some beer with our first Latvian visitors and waved good-bye to the officials. Igor stayed behind and asked us if we would like to visit his office in town? We all thought that this would be a good idea, quickly packed the boat up and followed him ashore to his car, we were getting quite used to rides in Trabants.

Wednesday 22nd July 1992 Shore leave in Liepaja

The office was sparsely furnished but the warmth of welcome was intense. "Do you need any sea maps?" asked Igor. "Do you have any for Estonian waters?" I enquired. "I show you" he said. A large stack of Russian admiralty charts was produced along with the coffee. I quickly thumbed through them almost holding my breath. Secretly I had been very worried about attempting the Muhu Vain, a channel through the Estonian islands, without proper charts. Now I had access to a complete set. They were all here, in great detail, the islands of Hiiumaa, Saaremaa, Muhu itself and Vormsi. "How much are they?" I asked. "$10 each?" suggested Igor. "That's very fair" I said and set about selecting the relevant ones.

They recommended a restaurant for dinner and Igor said he would try and join us. His colleague promised to bring some diesel round later in the afternoon. We thanked them for the coffee and charts and Igor drove us back to the dock.

The rest of the afternoon we spent wandering round the town and the fine beach. It is the largest town in western Latvia and was the birth place of the Latvian Social Democratic party. Sadly it suffered terrible bombing during the war as under German occupation it was an important submarine base. Despite the lack of grandeur though, there is still a faded elegance about its mostly wooden houses.

We didn't get to meet Igor that night as the restaurant was closed for repairs. We were given a lift to another by a charming Russian couple who arrived at the same time. Not only did they order the meal but, much to our embarrassment, they insisted on paying for it. More than anything else this act of generosity reinforced the belief that it's people that matter, not races.

Thursday 23rd July 1992 Liepaja to Riga

We had become spoilt by the good weather and now were expecting it as a matter of course. From Liepaja to Riga is about 200 miles which, given the right conditions, Elsinore can cover in 30 hours and so this was the plan for the end of our second leg.

The morning was bright and sunny though no wind to speak of, but with full diesel tanks and 43 hp that didn't concern me. I called up immigration on the VHF and by 8.30 we were motoring out of the main entrance. The Latvian Sailing Association people had warned us to keep well to the eastern side of the main channel as it had silted up but was not re-buoyed!

It was not until midday that the engine started to show signs of trouble. Just as it had done after Gdynia it suddenly faded away as if the prop was fouled. This time I knew it had to be either dirty diesel or water. Hoping it was the latter I drained some off at the water trap and bled the system. It started again and ran without a murmur, which was just as well as the wind, now from the north west was still light.

I had an admiralty chart of the Gulf of Riga which showed the southern channel from the Baltic to be rather narrow. My new Russian charts were more optimistic and showed much more detail, I just hoped they were right.

The sky clouded over in the afternoon which made the long sandy Latvian beaches we had been passing all morning not quite so attractive. We were still motor sailing and keeping up 6.5 knots average so that by 18.00 we were off the port of Vent-spils, altering course to follow the coast round to the East.

There are some sights and experiences that one remembers vividly from most sailing trips. As the sun set that night a beautiful gaff rigged yacht to the north and west of us was silhouetted against the bright orange sky. In the fresh breeze she had all sails set and charged across the horizon like a steam train.

The wind freshened up to a force 5 as we turned south east round the Kolka light guarding the Kol-kasrags point and so we reefed both sails for a quieter night. Despite the worry of the dead engine it was still quite exhilarating to be bowling along, down the Gulf of Riga with a fairly constant stream of shipping to keep us company. The large gaffer we had seen at sunset converged on our course and overhauled us. It was perfect Gwenilli weather and her look alike was making the most of it.

After breakfast Liz suggested cleaning the filters, despite them being of the disposable variety and theoretically unserviceable. Her farm experience had proved that a good wash in diesel can make a lot of difference. With no better suggestions to make I took both filters off, drained some diesel into a biscuit tin top and let Liz slosh them around. A good deal of dirt did come out which gave us hope that we were improving the situation.

I bled the system once again and with baited breath tried the starter. After a dozen turns it suddenly burst into life and I cannot begin to describe the lift that the sound gave us. It only lasted for a few minutes but that was probably air in the system that more bleeding would cure.

I spent the rest of the morning bleeding the air vent and retrying the engine. Each time it lasted a few minutes more but never enough for anything like comfort. Luckily the wind was still fresh and we were making good time on our dead run, it was parking that was the worry!

We entered the harbour at 12.30 and I called the harbour control for directions to the Latvian Shipping Company Yacht Club, the one recommended by Roger Foxall as being closest to the old town and the shops. The directions I got were unintelligible but luckily a passing pilot vessel called me up and told me that it was 10 miles up river on the port side next to the passenger ferry terminal. Ten miles meant a good hour's worth of air bleeding so I sank back into the bilges leaving Bryan and Liz to steer.

The Dvina river, on which Riga is built, became the means of access to the wealthy heartlands for invading Vikings and the point of outlet for traders wishing to export their riches from Russia. It was also the starting point for Arthur Ransome's maiden cruise in Racundra. I was a bit disappointed therefore to be missing it. However it is heavily industrialised all the way from the mouth up to the old town.

My efforts with the engine were not proving too successful so we kept sailing right up to the yacht harbour. The wind was still fairly fresh and as we would enter the harbour on a dead run Bryan dropped the main preferring to tackle the entrance with just the reefed genoa to worry about. If we had been allowed to stay at the first berth we picked all would have been well, but as we weren't and, with hindsight, dropping the main was a big mistake.

Having cleared immigration in the nearby passenger ferry terminal I did a lightening pack whilst Bryan chatted up the crew of the Danish gaffer to see if they could help with the diesel. My haste was because I was convinced it was Saturday and the last flight from Riga was 17.20, it being then 16.00. I made the flight, just, and got a wonderful aerial view of Riga as the Luftahansa Airbus circled over the town and river before heading south. The visibility was superb and as the flight path was along the Baltic coastline I was able to recognise and relive the just completed voyage.

Saturday 1st August 1992 Riga

With Peter Cockayne confirmed as my crew mate for the third and final leg, Liz and Bryan had decided to make their way home overland while I was in England. Liz's daughter had just arrived from New Zealand and Bryan was feeling homesick. Peter had left a note to say he had arrived and was now on a preliminary explore. I stowed my gear, awarded myself a gin and tonic and had just set about changing the oil filters when Peter arrived from his excursions. We chatted and dined on a huge meat pie, that Jackie had provided, and were entertained by a motorcade escorting the Danish Royal family back to their yacht which was parked the other side of the harbour wall. As we were not invited on board for night caps we decided to turn in ready for a long explore in the morning.

Sunday 2nd August 1992 Riga to Lehtma

The mouth of the Dvina river has been a choice sight for military strategists from the beginning of Empire building. The history books state that marauding Vikings built a complex of barns and storehouses there to act as a base for their invasions into the hinterland. Indeed some historians believe that the city's name is taken from the German version of "Rija", meaning bam.

Riga's rise to prominence accelerated when in 1282 it joined the Hanseatic League and became the main trading port in the Baltic, exporting amber, grain, furs, wax, honey, smoked fish and meats. Today it is known as "the Paris of the North" although years of Soviet occupation and neglect have taken their toll.

It is a fascinating place to visit with sharp architectural contrasts between communist utilitarianism and Gothic splendour. Peter and I exhausted ourselves exploring the old town as well as the new, and were surprised to be able to buy all the stores we needed despite it being Sunday. We agonised over buying a jar of what looked like mustard, but couldn't be sure. It was only when we realised that the price of a substantial jar was eight pence that we decided to risk it!

We got back to the boat at 16.00 and decided on the spur of the moment that, as we were foot sore, we may as well get going and do a night passage. By leaving in the early evening we should arrive at the tricky Muhu Vain the following afternoon.

We tidied up, ate some more pie and motor sailed out of the Yacht Harbour at 18.20. The harbour fees were $10 a night, and local currency was not acceptable. Considering the poor state of the facilities this was a real rip off, it did not though, spoil my tingling anticipation of setting off in the wake of Racundra.

Arthur Ransome and his crew, the Ancient Mariner and the Cook, left the Dvina at 10.00 in the morning. But an absence of wind and a reluctance to start the engine meant that they spent the best part of the day wallowing around in the fairway. At 17.30 despite several renditions of 'Spanish Ladies' Arthur was able to bathe from Racundra without any fear of her outdistancing him. It was not until 20.00 that the evening breeze set in from the SE and carried them out past the second fairway buoy.

We left the Dvina at 19.30 also in a flat calm but without any reservations over using the engine, which since the filter change was behaving itself. Racundra had made an anchorage at the island of Runo the next day but I was too pressed for time to contemplate this luxury. I wanted to reach and explore Tallinn, get the yacht to Helsinki, clear her stay in Finland with the authorities and find a trust worthy boat yard to look after her for die harsh winter, all in a week!

I was making up the plan as we went along being unsure of the reliability of the engine. At 20.10 it cut out but restarted after a bleed, it did the same at — 22.10 proving, we hoped, that as more air was bled off the frequency of failures diminished. The sky clouded over with sunset making it a dark night with the threat of wind and rain. We had been unable to obtain any weather forecasts in Riga so were sailing blind in that respect. My Finnish friend, Peke Saarela, had obtained a booklet from the Estonian Sailing Association giving details, in English, of all safe harbours and anchorages in Estonian waters. I was hopeful therefore of being able to find shelter should conditions warrant running for cover. The only critical part with no escape route was the 40 mile long Muhu Vain or Moon Sound that we should not have to enter until midday when I hoped the weather would have settled into a pattern.

By 2.00 we were 5 miles SE of Runo and could see its light-house quite clearly. Runo is the only island in the Gulf of Riga being almost equi- distant from Riga itself and the Estonian harbour of Parnu. During Ran-some's time it was home to families of Swedish seal hunters and now has a small harbour on its western coast but I suspect no seal hunters.

The wind appeared out of the south along with the first light of morning. It was a grey cloudy sky and a grey choppy sea but at least we could at last sail without worrying if the engine would hold out. At 5.301 spotted a strange looking object bobbing up and down on the waves which on inspection through the binoculars turned out to be a pedalo. What we were not sure about was if it was occupied or not, suppose their were bodies on board? We sailed as close as we dared in the now rough sea and, I have to admit, were relieved to find it abandoned. It was too big to take under tow in the conditions and so we left it bobbing along straight into the wind being proof positive that the currents are not totally induced by wind direction. I suppose we should have called up some coastal station and informed them of this potential hazard to navigation but were well out of radio range of the coast. The thought of trying to patch a call through via some passing ship without knowing the Latvian for pedalo was too much.

"The actual entrance is a couple of miles wide, with the little island of Virelaid on the western side and the larger mass of Werder on the eastern, each with its lighthouse. Then, though in some parts of it the shores recede and in places are over twenty miles apart, the actual channel narrows, twists and turns with such sharpness that big ships have gone aground through attempting a comer too fast or at a time when the current was too strong against them. I suppose there are few sections of sea chart on which so many wrecks are marked."

There are few pastimes I know of that even after years of repetition can still provide a genuine tingle of excitement that sailing new waters can. Our day was now sparkling with grey skies replaced by blue white flecks to the wave tops and the islands now taking on a rich greenness behind their sandy, rocky shores.

The channel was well buoyed and the GPS spot on so we were able to enjoy the passage with a minimum of worry. At the northern end of Muhu the channel bends to the north west which brought us hard on to the wind. We reefed down, started the engine for comfort and held our breath hoping to make the north bound channel without having to tack. In fact the engine was not needed and the beacons on the north side of Muhu which point to the start of the north channel were reached without incident.

All day we had only seen a catamaran going south in the early hours of the morning and were now quite alone. Roger Foxall had been refused permission to sail these waters because they were too dangerous and even Soviet yachts had to get written permission to pass through. I hoped that we were not transgressing some local regulations now but often ignorance is bliss so I did not worry about it.

The channels are indeed tortuous, "Twisting and turning like a hooked fish, heading first for this beacon and then for that and cutting through gaps that would make an eel think twice!" At 15.00 we saw our second vessel of the day, a ferry leaving Hal-termaa, a town on the eastern tip of Hiumaa, bound for Rohukyla on the mainland. It was good to see any vessel so long as it wasn't a gun boat complaining about our presence.

I now had to decide where we would spend the night, the wind was fresher than ever, still in the NW, and neither of us fancied another night at sea in these rocky channels. To the east, our favoured direction was the tiny harbour of Dirhami on the mainland, but the sailing guide advised that this was untenable in strong northerly or north easterly winds. As the wind had swung round from the south to the north west in half a day there seemed more than an even chance that it might continue to the north, so this was out. To the west on the northern end of Hiiumaa was the harbour of Lehtma, this was fine in anything other than a strong south westerly. Despite it putting another twenty miles on our route this seemed the safer bet.

The narrow channel got even narrower as we turned momentarily NE towards the island of Vormsi, (Worms in Racundra), before heading NW to skirt a 50 square mile area of rocks and shallows that blocks the southern approach to Lehtma. As we turned to the West the wind backed with us which was fine for our sailing but did not augur well for a comfy night as it was now blowing from the SW.

We approached the harbour mole at 18.30, keeping well clear of the shallows south of us. At 19.00 we turned into the harbour with the wind now gusting 16 knots straight out of the SW. Two Finnish yachts and one Estonian were plunging around at their moorings having made their sterns fast to some very substantial looking buoys. We edged in, picked up a stern buoy and then made the bows fast to the pontoon. With the help of our Finnish neighbours we managed to get another stern line secured to a buoy which, whilst not decreasing the motion, made us feel better.

A pretty young lady appeared on the pontoon, welcomed us to Estonia and asked how long we would be staying? "Just the one night" I replied. "But you must stay longer" she implored, "there is so much to see". I explained that we had to be in Tallinn in two days but promised to spend longer there on the way back. Slightly mollified she explained that there were showers, a sauna and a bar at the end of the jetty, and wished us a pleasant stay.

With Elsinore secure we took stock of our situation. The harbour was a wall which shut off the western side of a south facing bay. The shores were pleasantly wooded and in anything other than our present SW force 5 it would have been a pleasant spot. The newly built log cabin bar, showers and sauna were proof indeed that Estonia is really trying to appeal to the cruising yachtsman. For me it was wonderful to be anywhere on the other side of the Muhu Sound after a perfect day's sail.

Tuesday 4th August 1992 Lehtma to Dirhami

The wind was still howling out of the SW when we woke and Elsinore plunged up and down like some thoroughbred race horse desperate to be off. If she was keen, Peter and I were less so, for as well as the strong wind it was pouring with rain. Tallinn did not seem an attractive proposition so we decided to wait for conditions to improve before setting off. Our luck seemed well and truly out when we ran out of gas and our fitting would not screw into a spare bottle offered by our friendly Finnish neighbour.

The rain stopped mid morning and by 12.00 the wind had eased enough for us to test the plastic bung in anger. We started the engine, following many trials, hauled Elsinore back on her stern lines, dropped the port one and transferred the starboard one to her bow. Now head to wind we were able to hoist the main and sail off our lee shore in reasonable comfort. Our destination was Dirhami on the mainland about 25 miles away. Not a huge distance but it was in the right direction and should provide a much comfier berth in the strong westerly wind.

By 14.30 the sun was out and the wind had dropped to 12 knots. We were beginning to wish we had left first thing and made the passage to Tallinn, but you can't have everything.

Spotting Dirhami was not easy as the term harbour tends to exaggerate the actuality of the place. The superstructure of a fishing boat behind a low mole pin pointed the place but the entrance was a nightmare. Two buoys marked the narrow channel that was surrounded by rocks and breaking white water. I just hoped that the Estonian Sailing Association's sketch map which showed 3 meters minimum depth was accurate because we were not going to get a second chance.

All went well and we were able to sail into the lee of the mole without recourse to the engine. The fishing boat occupied all the sea wall and so we were forced to raft up alongside a Westerly Fulmar tied to the quay. It seemed strange to see a Westerly in the Gulf of Finland especially one flying an Estonian ensign.